|

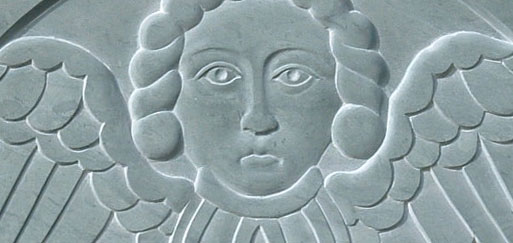

I was born in West Virginia and raised there and in Ohio. While not cut out to thrive in the academic world, my high school art instructor, Delmar Preston, saw something in me and gave me free rein in the art department. Every young person needs a taste of some success to give them confidence in themselves and so I took that outlook on to attend the Dayton Art Institute where I studied sculpture and design. This background qualified me for entrance level employment at the once world dominant Vermont Marble Company in Proctor, Vermont. There I advanced in what would be called the classic Italian sculptural method under the watchful eyes of the last remaining Italian sculptors still employed there. These old timers, with names like Tonelli, Palmerini, Carusi and Fox were part of a long lineage that started in Pietrasanta and Carrara and transferred to Vermont over the preceding century. These were production carvers who took an architect's specs and models and transferred them into stone to a tolerance of one thirty second of an inch. These were not gallery artists expressing their inner selves. These were the guys I worked with on additions to the U.S. Capitol Building, the Library Of Congress and the Dirkson Senate Office Building during the years between 1974 and 1978. We were not much different than the ancients who built the great architecture of the past. If you had dropped us into the stone age we would have had a job. The basic technique has not changed much. It's still a man with his hammer and chisel working from the model. I remember on one occasion when head sculptor Renzo Palmerini sat down next to me at the end of a day and remarked "You know my little buddy, all the great men are dead, and I'm not feeling too well myself." It cracked me up at the time but now after all these years, how true it was. I was born in West Virginia and raised there and in Ohio. While not cut out to thrive in the academic world, my high school art instructor, Delmar Preston, saw something in me and gave me free rein in the art department. Every young person needs a taste of some success to give them confidence in themselves and so I took that outlook on to attend the Dayton Art Institute where I studied sculpture and design. This background qualified me for entrance level employment at the once world dominant Vermont Marble Company in Proctor, Vermont. There I advanced in what would be called the classic Italian sculptural method under the watchful eyes of the last remaining Italian sculptors still employed there. These old timers, with names like Tonelli, Palmerini, Carusi and Fox were part of a long lineage that started in Pietrasanta and Carrara and transferred to Vermont over the preceding century. These were production carvers who took an architect's specs and models and transferred them into stone to a tolerance of one thirty second of an inch. These were not gallery artists expressing their inner selves. These were the guys I worked with on additions to the U.S. Capitol Building, the Library Of Congress and the Dirkson Senate Office Building during the years between 1974 and 1978. We were not much different than the ancients who built the great architecture of the past. If you had dropped us into the stone age we would have had a job. The basic technique has not changed much. It's still a man with his hammer and chisel working from the model. I remember on one occasion when head sculptor Renzo Palmerini sat down next to me at the end of a day and remarked "You know my little buddy, all the great men are dead, and I'm not feeling too well myself." It cracked me up at the time but now after all these years, how true it was.

Soon after the company was sold to the multinational giant OMYA who were only interested in grinding up our marble into dust so it could be used as an industrial filler for plastics, paper, and even diapers. The chain of continuity and skill passed down for generations was broken and the men sent away. It was hardest on those old timers.

I was young enough to learn associated skills which I added to my portfolio, and over the years established myself in the building trades as a specialist in stone and masonry construction and restoration. I've worked on many a public and commercial building, replacing aging ornamentation by using duplicated models I have built from the remnants of the old. I learned a lot about how the world works outside of the stone shed and this experience has been valuable to me. Since the advent of the internet I have been free of brokers, dealers, general contractors and job managers, so now I can connect directly with my customer base unencumbered by their expense. These days I labor away in my studio here on the farm in Vermont doing custom memorials and architectural carving for people all over the country. It's a rewarding life to see at the end of the day something real in front of me that will be around for people to admire for generations to come.

As I work I hold in my hands the tools that were passed on to me by the men who taught me how to master the trade and I often think about them and wonder who will hold these tools when I'm gone. Not many young people today seem interested in spending the better part of a decade learning to master traditional stone carving and I guess I can't blame them. But they are missing a real life experience. Renzo may have been right, and we are the last of a vanishing breed.

|

I was born in West Virginia and raised there and in Ohio. While not cut out to thrive in the academic world, my high school art instructor, Delmar Preston, saw something in me and gave me free rein in the art department. Every young person needs a taste of some success to give them confidence in themselves and so I took that outlook on to attend the Dayton Art Institute where I studied sculpture and design. This background qualified me for entrance level employment at the once world dominant Vermont Marble Company in Proctor, Vermont. There I advanced in what would be called the classic Italian sculptural method under the watchful eyes of the last remaining Italian sculptors still employed there. These old timers, with names like Tonelli, Palmerini, Carusi and Fox were part of a long lineage that started in Pietrasanta and Carrara and transferred to Vermont over the preceding century. These were production carvers who took an architect's specs and models and transferred them into stone to a tolerance of one thirty second of an inch. These were not gallery artists expressing their inner selves. These were the guys I worked with on additions to the U.S. Capitol Building, the Library Of Congress and the Dirkson Senate Office Building during the years between 1974 and 1978. We were not much different than the ancients who built the great architecture of the past. If you had dropped us into the stone age we would have had a job. The basic technique has not changed much. It's still a man with his hammer and chisel working from the model. I remember on one occasion when head sculptor Renzo Palmerini sat down next to me at the end of a day and remarked "You know my little buddy, all the great men are dead, and I'm not feeling too well myself." It cracked me up at the time but now after all these years, how true it was.

I was born in West Virginia and raised there and in Ohio. While not cut out to thrive in the academic world, my high school art instructor, Delmar Preston, saw something in me and gave me free rein in the art department. Every young person needs a taste of some success to give them confidence in themselves and so I took that outlook on to attend the Dayton Art Institute where I studied sculpture and design. This background qualified me for entrance level employment at the once world dominant Vermont Marble Company in Proctor, Vermont. There I advanced in what would be called the classic Italian sculptural method under the watchful eyes of the last remaining Italian sculptors still employed there. These old timers, with names like Tonelli, Palmerini, Carusi and Fox were part of a long lineage that started in Pietrasanta and Carrara and transferred to Vermont over the preceding century. These were production carvers who took an architect's specs and models and transferred them into stone to a tolerance of one thirty second of an inch. These were not gallery artists expressing their inner selves. These were the guys I worked with on additions to the U.S. Capitol Building, the Library Of Congress and the Dirkson Senate Office Building during the years between 1974 and 1978. We were not much different than the ancients who built the great architecture of the past. If you had dropped us into the stone age we would have had a job. The basic technique has not changed much. It's still a man with his hammer and chisel working from the model. I remember on one occasion when head sculptor Renzo Palmerini sat down next to me at the end of a day and remarked "You know my little buddy, all the great men are dead, and I'm not feeling too well myself." It cracked me up at the time but now after all these years, how true it was.